Publication and article by Ruth Soenen (Simply Community), Eva De Bruyn en Dieter Leyssen (51N4E Acte).

Download a pdf version of the publication from Team Vlaams Bouwmeester, or order a physical copy via press@51n4e.com.

Read the article (in dutch) in tijdschrift Publieke Ruimte.

Public space is where the desires, uses and needs of an unlimited number of users converge. Finding the right balance is not easy. Policy makers are faced with increasing complexity, but also with polarization and fear of change. Aligning spatial interventions with social realities is therefore essential. How can we ensure that the public realm is a space for diverse users? How can a street, square or park become a place where people can come together in different ways? To formulate answers to such questions, it is important to identify these desires, uses and needs. Integrating different perspectives, both from a helicopter view and from the residents themselves, is the necessary starting point for creating space for diversity.

As architects and anthropologists at 51N4E Acte and Simply Community respectively, we have worked together on several cases that have paid particular attention to diversity and public spaces. What follows is a combination of these perspectives in a multifaceted examination of space for diversity.

Why commit to space for diversity?

The challenges facing local authorities in relation to public spaces are great. Urgent social issues such as climate, wellbeing and mobility are reflected in the redevelopment of squares, streets and parks. On all these issues there are many views and a growing polarization. Challenges such as flooding and drought call for more permeable land, buffering capacity and strategic choices about whether or not to build. Different housing practices, movement patterns and living habits lead to different uses of public space - sometimes leading to conflict, with councils having to constantly make trade-offs. Do we provide benches, or do we rather take them away because they lead to nuisance? Do we allow residents to park in front of their doors or further away from their homes? Is there room for young people, and where should it be? Should interventions in the public realm focus on a particular neighbourhood or on a wider area?

Diversity in the broadest sense is an existing reality that we cannot avoid. Terms such as super- or hyper-diversity refer to differences of origin within the population. Then, there are differences in age, habits, or neighbourhood between people in the same municipality or city. Dealing with diversity is a necessity, but not always obvious. With increasing segregation and polarisation between groups and viewpoints, an integrated attention to diversity is essential to achieve a supported project, when thinking about the design of public spaces.

What makes a space fit for diversity?

To begin with, we want to focus on the unifying potential of public space. To do this, we focus on the use of this space through anthropological research into the interaction of people in public spaces. Public space is a daily gathering of quite different human profiles, a specific form of community that is not necessarily based on a collective identity. People are not bound together by a shared vision, religion, or moral values, but by a very ordinary, everyday social practice. We call this the small encounter. (1)

People can be together in different ways: on the basis of recognisability and homogeneity, but also on the basis of ambivalence and diversity. (2) Whereas architecture for communities often focuses on recognisability - being able to be together with people you know by sight - and homogeneity - being able to be together with peers - we particularly want to explore the third category within spatial design: being together on the basis of diversity and ambivalence. How can we give a diverse audience a place in space? What comfort is needed to enable use for all? How can we inscribe the handling of diversity in spatial design? Where together? How together? But also: where separately and how separately? The small encounter in the public domain is a dynamic balancing act between meeting and avoiding, between known and unknown, between familiarity and new adventures.

What is the approach?

Through studies for the cities of Antwerp, Bruges, Genk and Ghent, we developed a methodology that interweaves spatial design and anthropological analysis. The aim is to arrive at nuanced project definitions for (peripheral) urban transformations. A good example is the study work on the neighbourhood structure sketch for the Moscou-Vogelhoek district in Ghent: here we are in the urban periphery, a different context from the urban one. The issue of space and diversity comes more sharply to the fore here and there is increasing need for a renewal of the public space.

The process starts with the search for people and their stories. Through ethnographic research methods, we trace the story of the neighbourhood. We take the time to be present on site and observe the ordinary lives of residents. Typically for the fine-grained view of Simply Community, we do not enter the neighbourhood through the main entrance but through the side one. We listen not only to the usual suspects, such as presidents of associations, coordinators of NPOs, well-known neighbourhood groups, but also to less visible and unorganized residents. We pay special attention to this silent majority - those whose voices are not heard through online platforms, participatory workshops, and surveys.

We then process the collected data through a meaning analysis into a strong narrative, an anthropological working method about the neighbourhood and its diversity of resident profiles. A strong story connects to people’s immediate experience but also includes new perspectives to look at other local contexts. What residents tell is not simply represented in a strong story, but is assembled in a new way according to an analysis of the meaning of social phenomena. The new insights from the strong stories are place-based, detailed and fine-grained, but - and this is very important - non-specialist.

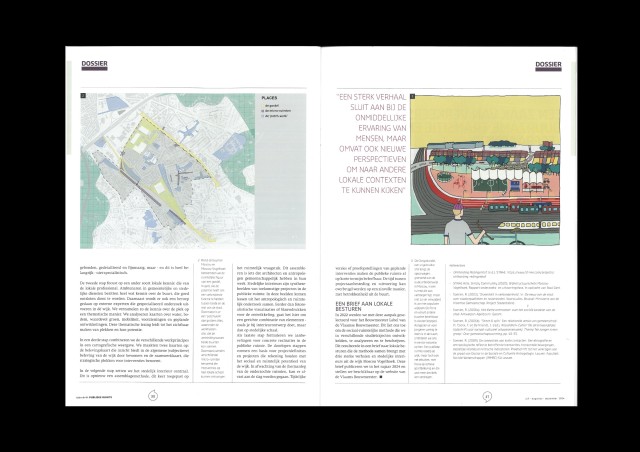

The second step focuses on a different kind of local knowledge: that of the local professional. Officials in municipal and urban services possess a great deal of knowledge about the neighbourhood, which needs to be properly accessed. We also call on external experts who conduct specialised research in the neighbourhood. We thus collect knowledge about the place in a thematic way. We analyse maps on water, soil, valuable greenery, mobility, facilities, and planned developments. This thematic reading leads to making places and their potential visible.

In a third step, we combine the different working principles in a cartographic representation. We produce two maps: the perception map, which gives an insight into the general (subjective) perception of the neighbourhood by the residents, and the framework map, which identifies strategic locations for interventions.

In the next step, a method called the urban interior, is central. This is again an assembly method, this time applied to space. This assembling is something that architects and anthropologists have in common in their work. Urban interiors are synthesis images of future projects in public space. These images bring together insights from anthropological and spatial research. They are not photorealistic visualisations or development plans, but a focused combination of elements - as in interior design, but on an urban scale.

As a final step, we formulate recommendations for concrete implementation in the public space. The completed steps form the basis for project definitions and projects that take into account the social and spatial potential of the neighbourhood. However, in anticipation of the renewal of the studied public spaces, transformation can already begin. Temporary or mock-up versions of the planned interventions allow the public space to already be experienced in the short term. The time between project tendering and implementation can be bridged in a meaningful way with the involvement of the neighbourhood.

A letter to local governments

With this approach, we were selected for the Flemish Bouwmeester label in 2022. This allowed us to analyse and describe the socio-spatial method we developed in several study paths. This resulted in a letter to the local authorities that combines the method with three strong stories and urban interiors from the Moscou-Vogelhoek neighbourhood. We will publish this letter in autumn 2024 and make it available on the website of the Flemish Bouwmeester.

References:

Ontharding Redingenhof (n.d.). 51 N4E. https://www.51n4e.com/proJects/ ontharding-redingenhof

51 N4E Acte, Simply Community (2020), Wijkstructuurschets MoscouVogelhoek, Rapport onderzoeks- en uitvoeringsfase, in opdracht van Stad Gent

Soenen, R. (2003), ‘Diversiteit in verbondenheid’. In: De eeuw van de stad: over stadsrepublieken en rastersteden. Voorstudies. Brussel: Ministerie van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap. Project Stedenbeleid.

Soenen, R. (2006a). Het kleine ontmoeten: over het sociale karakter van de stad. Antwerpen-Apeldoorn: Garant.

Soenen, R. (2006b). “Stitch & split’. Een relationele versie van gemeenschap’. In: Cockx, F. en De Vriendt, J. (red.), WisselWerk-Cahier ‘06 (driemaandelijks tijdschrift voor sociaal-cultureel volwassenen werk). Thema ‘Ne zanger is een groep’: Over gemeenschapsvorming, pp. 40-55.

Soenen. R. (2009). De connecties van korte contacten. Een etnografie en antropologische reflectie betreffende transacties, horizontale bewegingen, stedelijke relaties en kritische indicatoren. Proefschrift tot het verkrijgen van de groad van Doctor in de Sociale en Culturele Antropologie. Leuven. Faculteit Sociale Wetenschappen (IMMRC) KLJ Leuven.