Ahead of his keynote address at the 2025 Australian Architecture Conference, Dieter Leyssen, an architect, urban sociologist and partner at 51N4E, sits down with Felicity Stewart to discuss experimentation, autonomy and collaboration in a self-steering collective. Originally published in Architecture Bulletin, vol. 82, no. 1.

Felicity Stewart: I understand 51N4E is a self-steering collective, what does this mean, and could you please tell us more about how 51N4E was formed?

Dieter Leyssen: 51N4E has always put the emphasis on collective intelligence when making architecture, even when it was still small and long before I became part of it. The choice of name, 51N4E, or the coordinates of Brussels the place where it emerged, already holds that promise. Not the names of the founders but a place, a city. Now we are around 70 people big, and it remains to inject collective intelligence in our projects in a rather horizontal way. In that sense, all 70 of us are steering the direction of our practice.

Of course, with the growth and diversity of projects we’re involved in, this requires more organisation and infrastructure. Over the past ten years, we have experimented a lot with the space we work in and share, but also in developing shared tools to run projects and teams in autonomy yet in a shared culture. This gave rise to a company structure of different studios which are smaller companies that share a common infrastructure across projects. In 2020, just before the pandemic, we internally launched ‘51N4E becomes many’ and now this is gradually becoming reality. But it’s a constant work-in-progress.

FS: What is the scale of your practice and what is unique about the way you work?

DL: I think what’s quite unique at 51N4E is the attention and care for our projects and the dialogue from which they emerge. We structure our design process generally through workshops with our clients, project stakeholders, and partner offices where everyone enters the discussion and contributes their knowledge. Of course, a lot of work is done in the office, but it’s at these workshops that projects are made. Perhaps that’s why our projects are all quite distinct. People say we don’t have a signature style. All of our projects have different clients, users, conditions, informing the design. Also, internally a similar attention for moments of interaction is present. For instance, every year, for the last five years, we have met to discuss our year plan. What are the types of projects we want? What investments will we make for the group? Or another format, the agora, which is where we discuss more sensitive topics related to our practice. For instance, we recently discussed the language of sustainability and the risk of greenwashing unsustainable practices in our field.

FS: How would you characterise the main issues facing architects and urban designers in Brussels as a city?

DL: The main issue we are dealing with is undeniable climate change. Global warming and its effects in plain sight requires a reorientation of architectural and urban planning practices. And this is happening at a rather fast pace – new construction materials and recycling practices are emerging, increased knowledge on the lifecycle of materials and infrastructures and operational carbon footprint of buildings. Of course, it goes too slow and too little, but at the same time it’s also an exciting time to be an architect or urban designer. Our education did not teach us this, so we need to permanently educate ourselves and find complementarity in other fields.

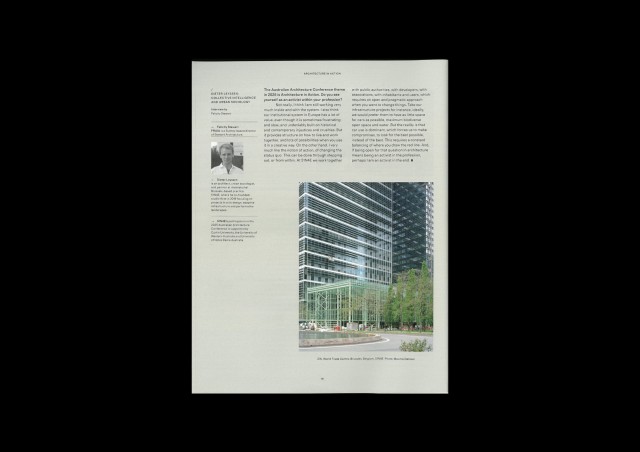

In Brussels specifically, the emphasis lies strongly on the reuse of former office stock in order to avoid the embedded carbon footprint of new buildings. With the arrival of European Institutions in the second half of the past century, a lot of offices were built that, gradually, are becoming empty because of a shift to a more efficient use of space. The Brussels Bouwmeester has been advocating a reuse for housing, where there is a need, and facilities leading to a wave of renovations of old structures in the European Quarter and North Quarter – the two most important business districts in the city. In doing so, these will hopefully become less monofunctional and connect parts of the city, while also saving carbon.

FS: How does operating at an urban scale shape your approach to design, and what opportunities does it unlock beyond conventional architecture?

DL: I am trained as an architect and always had a strong interest in the urban scale even as a child. But after my first five years in practice, I noticed that I didn’t have the proper tools to understand and work with. In general, I saw that architecture often lacks the understanding of social and economic realities of a site. After my training in urban sociology, and by getting introduced to the writings of Iris Marion Young, Rahul Mehrotra and Fran Tonkiss, this understanding grew. I think the opportunity of the urban scale lies in the relations a project or intervention can have with its context, spatially but also beyond the spatial. Sometimes a question does not need an architectural response, and I think that’s still hard to accept within architecture.

FS: What projects are you currently focused on? What excites you about them?

DL: Last year we opened a series of projects in Brussels and it’s exciting to see them come to life. There is a project for a farm in the outskirts of the city [Ferme du Chaudron], where different organisations working on sustainable food production share space and facilities. We also opened a new recycling facility [Recypark], combined with a skate park, alongside a canal. The wooden structure is partly made of a former horse stable and creates a big roof over the two uses. Then there’s the ZIN project, the former World Trade Centre of Brussels that we turned into a hybrid of offices, housing, and hotel facilities. And lastly, the renovation and reprogramming of the former railway museum inside the Brussels North station. Named TRACK, it’s a place we share as 51N4E with eight associations from the district for exhibitions, events and gatherings. To share an architectural and urban practice with organisations working on education, art, food and digital skills, inspires me every day.

FS: The Australian Architecture Conference theme in 2025 is Architecture in Action. Do you see yourself as an activist within your profession?

DL: Not really, I think I am still working very much inside and with the system. I also think our institutional system in Europe has a lot of value, even though it is sometimes frustrating and slow, and undeniably built on historical and contemporary injustices and cruelties. But it provides structure on how to live and work together, and lots of possibilities when you use it in a creative way. On the other hand, I very much like the notion of action, of changing the status quo. This can be done through stepping out, or from within.

At 51N4E we work together with public authorities, with developers, with associations, with inhabitants and users, which requires an open and pragmatic approach when you want to change things. Take our infrastructure projects for instance, ideally, we would prefer them to have as little space for cars as possible, maximum biodiverse open space and water. But the reality is that car use is dominant, which forces us to make compromises, to look for the best possible, instead of the best. This requires a constant balancing of where you draw the red line. And, if being open for that question in architecture means being an activist in the profession, perhaps I am an activist in the end.