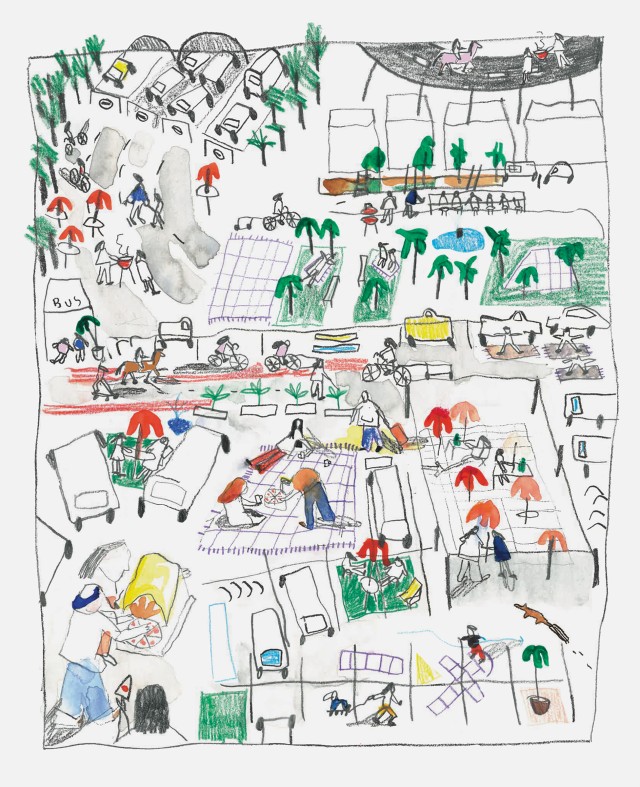

Barbecues on Asphalt, 2020

Article

Article by Dieter Leyssen, drawing by Chloé Nachtergael

Originally published on Desired Spaces: Future Scenarios for an (un-)built environment. View the original article here

The summer of 2020 looks like it will be one when citizens claim their public space. After months in quarantine, we are gradually discovering the sun-drenched parks, boulevards and squares in our towns and cities. The petition to stop traffic using Ter Kameren Wood in Brussels is just one of the many initiatives in a movement spreading across the country. And with good reason: as a result of social distancing, public life will probably take place outdoors more than at any other time. Let’s make use of this momentum to experiment to the full in the policy on public space: with multiple uses for streets, alternative uses for infrastructure (such as having barbecues on a viaduct, but more about that later) and private open spaces used as public areas. If we venture to look beyond a number of contradistinctions that have become established and which in the past often hindered change, opportunities for this crop up everywhere.

The first contradistinction it is better to avoid is that between city and countryside. We have heard that because of this crisis city-dwellers would from now on be opting more often for a house with garden in the countryside (Pascal De Decker in De Standaard, 9 May) and that the bustle of city life would be passé. This sort of framing of city and country as opposites is outdated. Whereas in the 1950s migration from the city sullied a Belgium that was virtually unsullied in its rurality, there is now simply no room left to introduce that model again. The future is urban and that, ironically enough, is also the only future for the countryside. After all, they both suffer from the same ailments. Excessive fragmentation, the undervaluing of green space and one-sided functional use lead to a paucity of good-quality public space. If we attempt to improve this, we end up with a similar approach in both cases. In both the city and the countryside, streets and squares can be used for much more varied purposes and shared more. So let’s look around at the space and infrastructure that’s already there and reflect on what else we can use it for, going beyond that single specific function for which it was constructed. In this way, all manner of unexpected possibilities turn up. Think of the canal that traverses Brussels and large areas of the country: you can see it as a transport route, but also as a bicycle highway, a site for biodiversity and public space for adjoining urban districts and residential estates.

So off to Brussels, where I live and work. During the lockdown, pedestrians and cyclists dominated the city’s streets for a while, which were free of cars and tourists. But sadly we also saw that the effervescent life of the city came to a standstill, without its countless cafés, tearooms, markets, events, museums and shops. This takes me to the next contradistinction that is to be avoided.

Sometime in the early twentieth century we started dividing streets and squares into zones, neatly categorised for cars and ‘vulnerable road users’. This contradistinction is also increasingly becoming unusable. Streets and squares have become monopolised by one single mode of transport. But cars, pedestrians and cyclists intersect in a natural way, especially in city centres. Tunnels and complex crossroads have been built in an attempt to soothe the pain, but at the expense of spacious squares and boulevards. As a result of the obsession with moving efficiently from A to B, we forgot all the other dimensions of the street: reception, information, encounters, protests, emancipation, learning new things, and so on. You gradually start to wonder whether, in an attempt to make things clearer, we have not made it all much more complicated. Would it not have been better to understand that public space is de facto shared space?

If we are not careful, we shall fall into the same trap once again. New forms of zoning are making their appearance: squares for events and bicycle highways, for example. A pedestrian zone cannot in all conscience be so labelled until it has been paved with bluestone and punctuated with young trees. In recent years a lot has again been invested in the compartmentalisation of public space.

There are other possibilities, however, needing only limited resources and without endless building sites. Every evening and weekend in Sao Paolo, the Minhocão viaduct – one of the most important traffic routes through the city – becomes a huge terrace for city-dwellers who live in cramped accommodation. Clever management gives this one piece of infrastructure a new meaning. And it’s just as easy to barbecue on asphalt. Examples such as this show how the monopolisation of public space initiated in the last century can be phased out. With only limited investment, streets and squares provide space for several aspects of city life. What about a Sunday picnic in Wetstraat from now on, with more room for cars again on Monday? Why not?

Lastly, the contradistinction between public and privatised space. This issue has frequently impeded the improvement of Brussels’ public space. Think for example of the pavement cafés on the St Katelijneplein square and the absurd situation surrounding Guldenvlieslaan (one plan was drawn up by the public authorities and another by the neighbouring retailers). Public and private are however not mutually exclusive. Inhabitants and tradespeople can arrange with the local authority to take responsibility for the use and management of public space. In this way, unused verges and fragmented patches of greenery can become shared vegetable gardens. The depaving projects supported by the Flemish authorities are a good example of this. In this way, they encouraged residents to appropriate their public space: a policy that stimulated them to think of everything that might be possible rather than defining what was permitted or not.

But the reverse should be possible too. It should also be possible to give private open space a public use. In many towns and cities, the public authorities are no longer the only body responsible for the creation of public space. After all, good, multipurpose public space always benefits private property. When they take this view, developers themselves sometimes take the lead in the creation of streets, squares and parks. It’s true that clear sets of agreements are needed to avoid other, ‘private’, rules being applied different to those elsewhere in the city. A good example in Brussels is the abattoir site in Anderlecht. On this ‘Abattoir’ land there is a market in the weekends and throughout the week socio-cultural projects involving the youngsters associated with Culturegem. The whole place is also freely open to passers-by and local residents. So this is a friendly call to all landlords, developers and the authorities to cooperate on new types of public space that make room for a good quality of life, culture, economic activity and activism, by bringing citizens’ groups, cultural institutions, artists and local residents into the picture too.

In spite of the grim economic prospects, the proactive policy on public space seen over the last few weeks gives me hope. In the time to come, a substantial difference can be made in the way our diverse society experiences, co-creates and manages its streets and squares. When we go beyond the contradistinctions, a new approach may take shape in which, rather than waiting for change, change becomes part of a collective learning process. If we can start now, why are we waiting?